René Girard & Mimetic Theory for Non-Philosophers

May 2020

Mimetic theory is a simple but immensely powerful concept. It explains how humans learn, why laws exist, and why too many people want to go into Finance. The idea was developed by René Girard, a french philosopher, member of the Académie Française and professor at Stanford. In the last few years, independent of Girard’s research, studies into imitation, formation of desire, and mirror neurons have been published that bring forward empirical justification for the theory. Let’s start by looking at the core concept of mimetic theory: Imitative desire.This is the primer I would have wanted to read before diving into the primary literature, which is eye-opening but can be dense.

Figure 1. (Emotionally) violent imitation in monkeys [src]

Figure 1. (Emotionally) violent imitation in monkeys [src]

Mimetic desire

According to Girard, spontaneous desire is an illusion. Our own desires are formed by imitating the desires of others.Mimesis just means imitation. Girard uses ‘mimesis’ to differentiate it more clearly from Sigmund Freud’s ‘imitation’. As we will see, Girard’s imitation is much more conflictual and violent than Freud’s. We copy from the people we admire (a mentor or a famous person) and from the people that are most like us (our fathers or our colleagues at work).Advertising shows desirable (= imitable) people wanting what the company wants consumers to want. This Mimesis is pre-conscious; we’ve cloned our model’s attitudes and desires before we’re even aware of it. While imitation can lead to negative and violent outcomes, it is also vital for learning and for figuring out what to do with our lives.

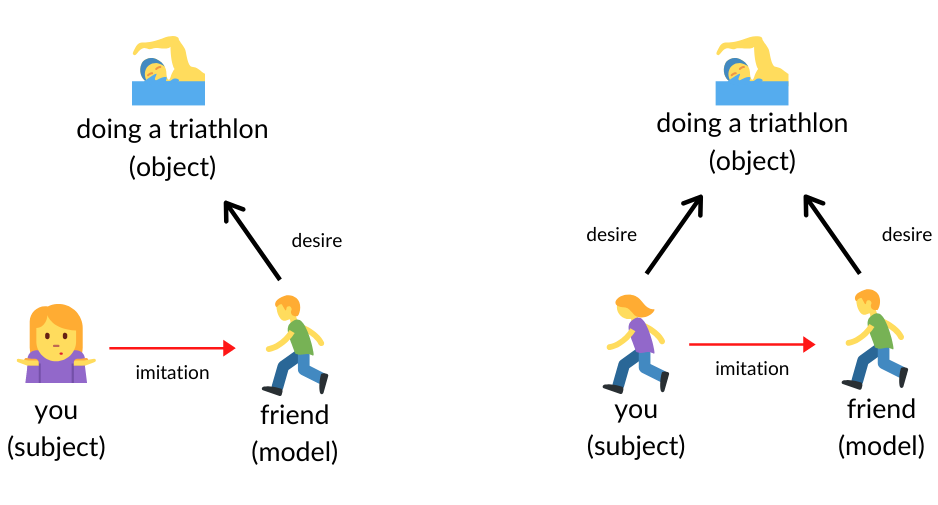

Let’s look at an example of (beneficial) mimetic desire: you imitate your friend’s desire for partaking in a triathlon and join in on the exercise:

Figure 2. Your friend tells you about the triathlon he is training for and suddenly you feel inspired to do the same. This subject-model-object structure is called triangular mimetic desire.

Figure 2. Your friend tells you about the triathlon he is training for and suddenly you feel inspired to do the same. This subject-model-object structure is called triangular mimetic desire.

In the last few years, many researchers have been empirically investigating imitation. Their studies were performed independently of Girard, but the topics are very relevant to mimetic theory. They show just how prominent imitation is in young children and how mirror neurons relate to mimicry:

- Cultural learning: Children imitate the food, drink, and toy preferences that they observe in adults. This effect is stronger if the adult is perceived as more popular (study).

- Emotion matching: From a very young age, children imitate the emotional state of the adults they interact with (First published here and replicated since). It’s difficult to measure emotions in babies so their facial expressions were used as a proxy.

Peekaboo science [src]

Peekaboo science [src] - Mirror neurons: There are neurons in the brain that fire both when you perform a task and when you see someone else perform the task (Nature review). The task can be anything from eating a sandwich to grabbing an object to experiencing emotions like anger. These mirror neurons were first discovered over 25 years ago, yet they are still subject to much debate. There is an overall agreement that they exist but an ongoing dispute over their exact function in the brain (overview).

So there is a good amount of empirical evidence validating mimetic desire, the core mechanism in mimetic theory. In the next section, we’ll look at how imitating the desires of others can lead to problems.

Mimetic conflict

Mimetic desire doesn’t have to be problematic, but when the desired object is scarce it can lead to conflict. This scarcity can be physical (two children wanting to play with the same toy) or intangible (two colleagues eyeing the same promotion). Even initially productive imitation can become conflictual: The apprentice follows his master’s footsteps so closely that he ends up opening his shop in the same town. Some objects of desire are so scarce, they wouldn’t even exist if it weren’t for people pursuing them. Prestige and status are good examples.

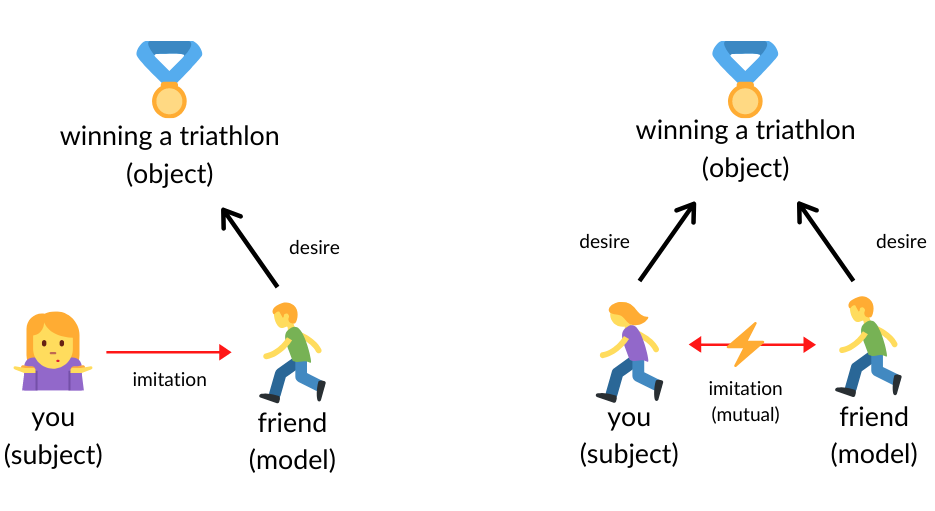

Going back to the triathlon example, let’s now imagine your friend being more ambitious. Instead of just participating, he now wants to win:

Figure 3. When the subject imitates the model’s desire for a scarce object (here a triathlon win) they run into conflict.

Figure 3. When the subject imitates the model’s desire for a scarce object (here a triathlon win) they run into conflict.

As we see, if the object of desire can only be possessed by a single person, the subject’s imitation of the model leads to conflict. Both are now competing for the same scarce resource. We’ve reached conflictual mimesis. At this point, if both parties are very competitive, the object of desire gets less relevant. The conflict stops being about acquiring the object and starts being about beating the other.

In a simulated competition like sports, the mimetic cycle might stop there. You might lose a friend but gain VO₂ max, so all is well. But what if the stakes are higher, if things get out of hand, and people become aggressive?

Girard says: People don’t stop imitating their model once they notice a conflict. Instead, both parties also mimic each other’s aggression, leading to a spiral of violence. And, thinking back to the studies on emotion matching, if each party convinces their friends to join in, then step by step the whole town is enraged.

Now, this doesn’t normally happen with innocent triathloning. But things are different in a vulnerable, primitive society during times where discontent is already ripe. There, violence can spread like a contagion,There are studies that look at how emotions spread through groups, albeit in more calm settings. This field of research is called emotional contagion. This paper shows how ‘children, regardless of their age, imitate the costly punishment of both equal and unequal offers, and the rates of imitation increase (not decrease) with age’. threatening to rip society apart: the mimetic crisis is building.

Developed societies like ours have measures protecting against escalating mimetic violence. Laws, religion, or societal norms protect us from some of the retaliation. Just because I beat up your brother doesn’t mean you’re allowed to beat up mine, and I might be thrown in jail. But such laws didn’t exist yet during our ancestors’ times. Yet human societies survived. So there must have been some way for our ancestors to stop the cycle of contagious brother-beating and pull themselves out of the mimetic crisis without complete destruction. Girard says they saved themselves by moving the blame onto scapegoats.

Scapegoats

Let’s imagine the worst-case scenario: a society where people are very equal (leading to more imitation) and generally on-edge (eg. during a famine). Some localized violence sparks, maybe family A steals family B’s sheep and family B retaliates by taking A’s first born. Every local settler takes a side, and through mimesis, the violence spreads quickly. Soon the whole society is unstable. So what did people do to save themselves from the mimetic crisis? Girard says instead of murdering each other, they looked for someone else to blame their outrage on - someone to scapegoat.

The perfect scapegoat would be part of society (else how could they have caused the outrage?), but sufficiently differentiated (too similar to us and we’d all be guilty). The victims are picked arbitrarily: maybe they are disabled, have red hair, or belong to an underrepresented religious group. The collective blaming of the scapegoat allows the community to direct all their anger at a single outlet. The victim is accused of having caused the escalation of violence (maybe they offended the gods or poisoned the waters). Now, instead of hurting each other, the community mimetically channels its hatred into the scapegoat. Then, in an act of collective catharsis, the scapegoat is murdered or otherwise gotten rid of.For this to work best, the whole society needs to take part in the punishment. This is why arcane societies often got rid of their victims in collective and public ways: ‘witches’ were burnt and ‘traitors’ stoned. Girard calls this the founding murder.

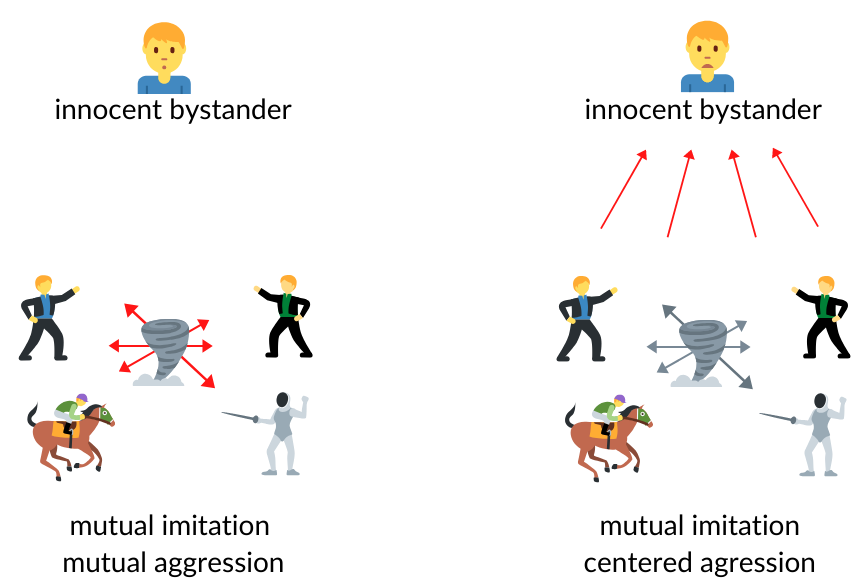

Figure 4. In a society where everyone is fighting, people imitate each other’s violence. By blaming a scapegoat, they can instead imitate each other’s aggression towards the newly found victim. Ultimately, getting rid of the scapegoat ‘solves’ the problem.

Figure 4. In a society where everyone is fighting, people imitate each other’s violence. By blaming a scapegoat, they can instead imitate each other’s aggression towards the newly found victim. Ultimately, getting rid of the scapegoat ‘solves’ the problem.

Now that the scapegoat is gone, the problem appears solved, and society can go back to functioning calmly. This founding murder represents a duality: people blame the scapegoat to have caused the escalating violence, yet the scapegoat (through the collective murder) also brought lost harmony back into society. Girard says this lays the foundation for a spiritualization of the scapegoat - it becomes a proto-god.

Wanting to relive the peace-bringing effect of the founding murder, societies come up with myths and rituals recapitulating this past event. Importantly one thing must never happen: It can never be known that the scapegoat was innocent.If it were known that the ‘witch’ is just a strange woman with red hair, the murder would just be an obvious act of unnecessary cruelty and not have any of the pacifying effects. Therefore the murder is covered up. Over time the real, brutal origins of the myth become forgotten and the ritualistic replayings of the founding murder become more obscure.The scapegoat theory is compelling and there are many exemplary myths. Girard often references Oedipus or myths from Frazer’s Golden Bough to prove his points. But since he argues that the murderers cover up their collective wrongdoing it is impossible to falsify. Found a myth without scapegoating? It’s just covered up too well. Found a myth with scapegoating? Evidence in favor. I haven’t read enough Popper to know what to think about that. All things equal, the peace bringing effect slowly fades and the cycle starts anew.

Conclusion

Luckily due to laws, norms and religion, ritualistic sacrifices are not part of our everyday life anymore. But there is no escaping the imitation of desires. So what do we do with that knowledge?

On one hand, mimesis can lead to conflict, especially in the presence of scarcity. Other people having the same goals seemingly gives our own desires validity.This follows the motto: something that is hard to do must mean it’s worth doing. Often the result is mindless, zero-sum competition without any actual progress.

On the other hand, mimesis can be insanely motivating and productiveGirard argues that capitalism is productive mimesis. People compete to everyone’s benefit and there is rarely actual violence. if you pick your models wisely. The ideal model shows you the way without offering any potential for conflict.e.g. by being far away, dead or fictional.

Further reading

After learning about mimetic theory I started seeing examples all over the place: in how students pick careers, in dancing, in advertising or in the way people act at work. Girard’s books are tough to crack but eye-opening. I suggest starting with The Girard reader and then moving on to Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World.